Bodog wrote:Cliff, reading this got me thinking about something. It's a given for most people that wear resistance is fairly equivalent to edge retention. But why is that?

Because they are confused and/or being mislead.

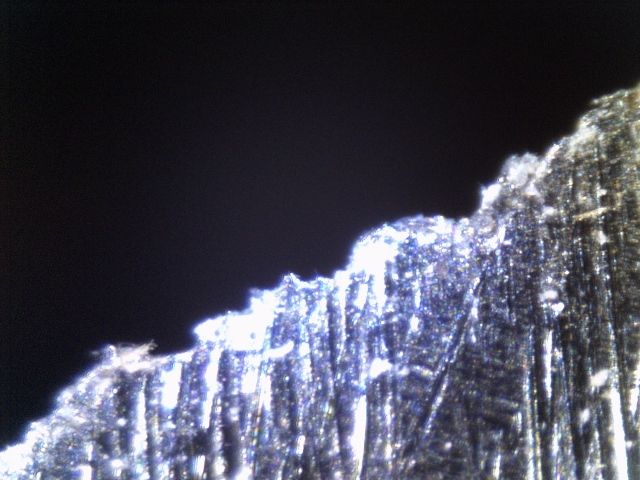

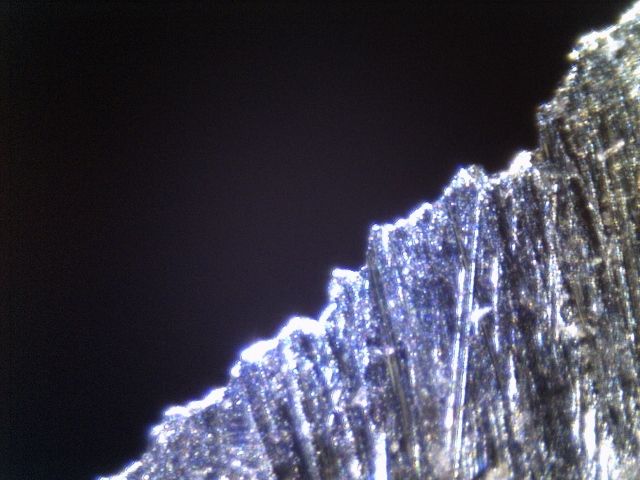

It has to be kept in mind that extreme carbide volumes in steels are not new, they are literally a hundred years old. As of late there has been a strong promotion of carbide volume in the small shop knife industry but this isn't true in industry because quite frankly it doesn't work. Now to be clear not every knife maker/manufacturer rejects metallurgy and many of them have come to the same conclusions independently. For example Jerry Busse was one of the first I saw argue strongly in public that a lot of carbide doesn't necessarily improve edge retention because he looked at a lot of blunted edges under magnification and he saw damage from fracture / deformation and carbide doesn't help one and makes the other worse. Hence, among other reasons why he moved from D2 to the steel he made semi-famous which is used in the industry for guess what - high impact wood cutting.

Carbide volume weakens a steel.

As you made a technical argument I am going to seriously geek out on some issues here language wise.

Inherently carbides are much harder and stronger than steel, for the alloy carbides this is to such an extent they are not even in the same class and have to be measured on a different scale. Comparing Tungsten carbide to martensite is similar to comparing martensite to wood. When you look at how adding carbides to steel effects strength you have to be very careful because it can both increase or decrease it depending on how you measure the strength. The two things to consider are :

a) the carbides are essentially infinitely strong compared to the steel which means they won't deform/bend during a load, and this is because

b) there is a bond between the carbide/steel and this bond is much weaker than the carbide itself and likely even than the steel itself

As a few general rules then :

-Adding carbide volume will increase strength in compression when the sample size is much larger than the carbides. This happens because it prevents the load from being isolated on a carbide (which can crack it) or from over loading carbide/steel bonds which can cause fractures.

-Adding carbide volume significantly doesn't tend to increase torsional or tensile strengths. The most dramatic view of this is for example raw carbide has an extreme compression strength but you can't even do a standard tensile strength as it will just crack if you try to secure it as it is so brittle.

Thus for very high strength steels measured in torsional, lateral or tensile, the carbide volume is very low. However for high compression strengths measured in a large scale then the carbide volume can be very high.

So, what is wear resistance in relation to edge holding capability?

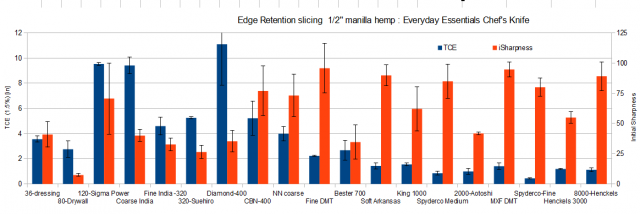

Wear resistance is actually measured in a number of different ways and while they are similar they are not identical. Wear resistance can be measured in abrasion or adhesion and under high load or low loads. S7 for example can have a higher wear resistance than M2 under high load abrasion as it resists fracture better. In general when wear resistance characteristics are talked about for knives they generally mean low load abrasion, though often manufacturers try to sneak in adhesion because it gives much higher numbers for HSS steels.

All it does is prevent the steel from metal loss by general abrasion (which is being cut essentially). Adhesion isn't usually a factor as you are rarely cutting metals with a knife. Now it it here where you might ask well how much do woods, ropes, foods, etc. actually abrade steel - not very much really which is why it doesn't matter nearly as much as people think compared to strength and toughness, but the latter is not as trivial as you might think in some cases.

One of the curious reasons why very high carbide steels can work well in some types of edge retention comparisons is that they actually do chip more and these chips give the edge a very low type of sawing sharpness. A steel like AEB-L will tend to wear smooth, ATS-34 will not. If you are doing mainly sawing cutting and you really don't like to sharpen and you use dull blades, then you likely would rather the ATS-34 blade because of how it wears to leave that more ragged edge which can keep you cutting at low sharpness.

This is why if you do cardboard cutting for example with AEB-L vs ATS-34 then the performance ratio will change if the cardboard is very soft, vs if it is really hard. The latter can tend to chip the edge and this can magnify the performance of the ATS-34 on a slice but reduce it faster on a push. Thus which steel performs better depends on how you are cutting, the type of cardboard and when you decide to stop (high or low sharpness).

I guess I'm asking, carbides and all that mess aside, wouldn't a normal person want the toughest steel at the highest hardness available if they were looking for stable edges?

At high sharpness levels, not necessarily for low sharpness levels.

I'll go easier, why would someone want 440V at 56 hrc over say, 52100 at 63 hrc (again, leaving corrosion resistance out of it)?

The thing to keep in mind is not everyone has the same preferences when it comes to knives. When I sharpen knives for the majority of people they are extremely dull. I can see the apex clearly, they have essentially no sharpness left at all and strongly reflect light. At times you can get a really biased view by just talking to people who are really into something and you forget that most people would not have even close to the same view.

If you go back to the metallurgy, then as the apex thickens, at some point it will be so thick that the carbides will no longer tear out, they will no longer have compressive bond fractures and the apex will start acting like a thick sample in testing. That is to say it will become extremely resistant to further wear, deformation and fracture. This is why people like Tom Mayo who made hunting knives for guides who always returned them for sharpening "bowling ball dull" strongly favored 440V at < 60 HRC because under those conditions it would in fact work much better than 1095 at 67 HRC.

Again, the first thing to always keep in mind is that you have to start from :

-what are the properties that the user wants/needs

only when this is known can you even start to think about :

-what are the properties needed in the material

The other thing to keep in mind is that the more correct you want the answer to be the more detail you need. In many cases people don't really want a sort of perfect answer they would be satisfied with an ok one. Thus for example if someone asked you about 420 vs ATS-34 then you might be as short as saying something like "ATS-34 is a premium knife steel, 420 is mainly used for inexpensive replicas - get the ATS-34". Now this really isn't strictly ideal advice in a lot of cases - but the person asking might not care about those details and may just want to know on a very general level.